Go as close as possible to the edge of absurdity without crossing it | Marcial Jesús - 100architects

- Doğukan Güngör

- Nov 24, 2025

- 13 min read

Updated: Nov 29, 2025

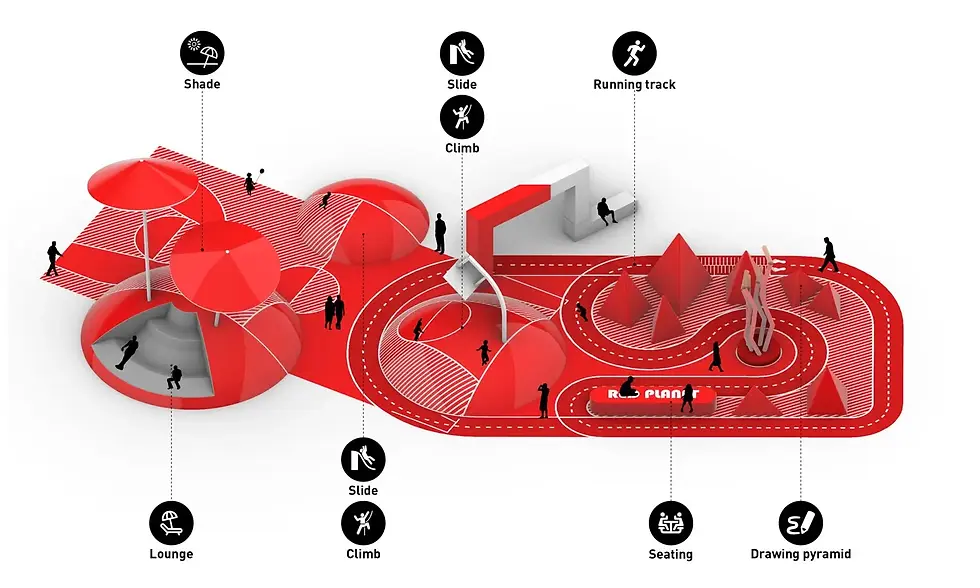

Shanghai-based architecture firm 100architects places the idea of turning public space into a playground at the heart of its design practice. With vibrant, interactive, and participatory projects, the studio has captured global attention. Guided by the motto “form follows fiction,” they approach architecture not just as a space, but as an experience.

In this interview, we spoke with Marcial Jesús, founder of 100architects, about what it means to design in the public realm, the influence of pop culture in their work, and the connection between architecture and play. A conversation full of inspiration — for both designers and urban dreamers alike.

Interview: Doğu Güngör

Photo - © 100architects

To start, we’d love to get to know you better. Who are the creative minds behind 100architects? What motivated you the most when you founded the studio?

I founded the studio when I was 25, January 2013, shortly after arriving in China. Before that, I had passed through Europe and worked in a few remarkable studios. First at Fuksas in Italy (2009), and then at OMA in Rotterdam (2010). That experience at OMA was fundamental; more than anything I could have learned, it truly inspired me.

The motivation came from a mix of things. Above all, I wanted to do something different — not the same architecture or the same buildings everyone else was doing. I wanted to skip a few steps and create something that could inspire me and inspire others. I knew I couldn’t stand out by offering what others were already offering; 100architects had to be born from a completely different seed.

At that time, I also understood that starting so young, without experience or contacts, I needed to be somewhere with strong winds — a powerful place that could help me fly far. That place was China, specifically Shanghai — the financial heart of Asia. A city where innovation is not feared, and where qualifications matter less than ideas. In Shanghai, people with good ideas can truly take off.

Those realizations led me to the concept of 100architects, a studio founded on the idea of doing things differently, of connecting architecture with people, and of bringing inspiration into the public realm. I was inspired then, and I still am today by what we do.

Today we see many creative interventions in public space, but your projects stand out with a unique approach to scale, color, and participation. How did this design language emerge? What question were you originally trying to answer?

As I mentioned before, the first realization was that I needed to do something that truly belonged to everyone, something that mattered to all. That immediately excluded houses or buildings, which only interest architects or developers. It had to be public space.

Then I understood that for something in the public realm to really matter, it needed to be both pop and controversial.

Pop, meaning easy to understand, easy to like, and accessible to everyone. And controversial, because public space belongs to all, and therefore must provoke debate, emotion, and engagement. It also needed to be disruptive, something that perhaps looked like it didn’t belong, yet gave identity to its surroundings. Those became the first ingredients of our design language.

Over time, we developed those properties further. We realized that public spaces hadn’t changed much for decades, but the users had changed completely. Especially children and not only them, but everyone. People today are used to a different kind of sensory stimulation, influenced by technology, gaming, and social media.

So we concluded that public space needed to stimulate people again, both physically and emotionally.

That led to our idea of hyper-stimulating architecture — spaces that are interactive, touchable, and approachable. They must invite users to jump, climb, sing, take selfies, and feel excited. They must allow people not just to enjoy nature, but to experience an enhanced version of the public realm.

From there, other principles naturally emerged — fantasy and surprise, inspired by narratives that transport users into a new world. We often say form follows fiction, because we use storytelling as the foundation of design. By borrowing iconography that already exists in people’s minds, we can connect instantly with their emotions. And color, of course, is a tool we use consciously, not decoration, but a communication device that captures attention and amplifies experience.

All these properties were shaped in our first years through experimentation, a constant process of trial and error, designing small interventions and installations in the public space. Those early exercises were our laboratory, where the DNA of 100architects’ design language was born.

From the outside, your work appears colorful, imaginative, and playful. But what is the inner world of the studio like? What kind of working environment awaits a designer who joins 100architects?

At 100architects, we work with a very horizontal structure when it comes to creativity. Ideas can come from anyone, sometimes from trainees, sometimes from senior designers, and often from spontaneous brainstorming sessions. Architecture in our studio emerges from constant dialogue: design reviews and creative discussions happen several times a day.

Photo - © 100architects

In terms of methodology, we’re not radically different from other architecture firms, but our real distinction lies in how open we are to ideas, and how far we’re willing to explore the thin line between the reasonable and the unreasonable.

That’s where our best ideas are born, in that fragile space between logic and absurdity.

The environment at the office is also quite relaxed. We work a reasonable amount of time, we don’t do overtime, and we don’t work on weekends, something rare in our industry. It may sound obvious outside of architecture, but it’s essential for our kind of creativity. To design the kind of projects we do, people need mental space, freedom, and energy.

We encourage everyone to reach for that difficult balance — to go as close as possible to the edge of absurdity without crossing it. That’s where a project can truly spark imagination and create wonder. We call it fantasy and surprise, and it’s at the core of everything we design.

Most of your projects introduce a new presence into the urban memory and have a strong visual impact. When developing an idea, how do you engage with the people living nearby? What kind of contextual foundation do you build your designs upon?

We always begin with a thorough site and context analysis, just like any architectural project. Even though our designs often look like they don’t belong — and that’s intentional — they are in fact deeply connected to their surroundings. The contrast you see in our projects is real and deliberate. We don’t aim to blend in; we aim to stand out. That differentiation gives identity to a place.

But while our projects may look like UFOs landing in the middle of the city, they are carefully tailor-made for each site. The strategy goes beyond visual impact. It’s rooted in the study of circulation, connectivity, and the conceptual DNA of the location. Every intervention responds to its context — socially, spatially, and functionally. So even if it looks extraordinary, it’s actually a contextual solution designed to meet the specific needs of that place.

When it comes to engaging with the people living nearby, this has become a growing part of our process — especially for large-scale public projects. For example, in some of the big parks we’re now designing in Dubai, we’re asked to involve local communities directly. We conduct workshops with nearby schools, where children participate in exercises and questionnaires that help us understand how they play, what they enjoy, and what kind of spaces they dream of.

These participatory processes are always done in collaboration with the client, since community engagement requires institutional coordination and trust. But this approach is becoming increasingly common in our recent work. It ensures that even our boldest and most unconventional projects remain deeply connected to the people and places they’re designed for.

How do your collaborations with local governments or private stakeholders usually unfold? While producing such bold and attention-grabbing work, do you face challenges such as bureaucracy, limitations, or a lack of vision? Are there moments when your motivation fades? Is it difficult to find project partners who are as brave as your concepts require?

We work with three main types of clients, and each collaboration unfolds differently.

The first group is real estate developers. We help them inject fresh, eye-catching public spaces into their residential developments — spaces that make their projects stand out in a saturated market. These interventions not only enhance the quality of life for residents but also contribute to faster sales and higher property values.

The second group is commercial operators — clients who manage retail streets, malls, or entertainment areas. With them, we focus on transforming shopping into an experience. In a world where online shopping is cheaper and more convenient, the physical retail environment must offer something digital platforms cannot: real-life interaction, atmosphere, and excitement. That’s where our designs come in — creating immersive, memorable spaces that attract people and keep them coming back.

The third group is local governments. With them, our work revolves around city branding — helping municipalities create urban landmarks that attract tourism, increase footfall, and put their cities on the map. These projects often become powerful tools for identity and pride.

Now, regarding the challenges — yes, we face plenty. Bureaucracy, limitations, and lack of vision are constant companions. But that’s part of our job: to convince, to inspire, and to bring others on board.

In fact, many times our clients’ constraints push us to find more grounded and practical solutions. A great project always requires a great architect and a great client; one cannot succeed without the other.

Of course, there are moments when motivation fades — when decisions are made beyond our control, or when last-minute changes alter what we envisioned. It happens in almost every project. But this is a long journey, not a sprint. Over time, we’ve learned that the more we grow, the better the partners we attract. Better contractors, better clients, and more people who truly value our vision. It was extremely difficult in the beginning, and it’s still challenging today — but each step brings us closer to building better cities together.

How much do randomness and intuition play a role in your design process? Is everything pre-planned within a structured system, or do you eventually trust the flow of instinctive decisions? How do you balance rational planning with spontaneous creativity?

Our design process is deeply intuitive — especially in the early stages. I love to throw lines into a proposal, sometimes without knowing enough and fully risking the absurd, as I mentioned before.

Traditionally, architecture is understood as something that must be fully rationalized — I remember teachers in university saying you should be able to write a book about your project before designing it. We do quite the opposite. While we value site understanding and contextual analysis, we also dare to overlay ideas that may seem irrational or even out of place at first.

It’s in the intersection between ideas, where logic meets nonsense, that we often find something new — a sweet spot close to absurdity but still functional and meaningful. That’s where surprise is born.

At 100architects, intuition plays a huge role. We’ve developed a way of testing ideas very quickly, in a visceral way — almost from the gut. We explore things that many architects might not even consider at first. By trusting intuition early on and then confronting it with rationality as the project matures, creativity is released.

That’s when we discover neglected possibilities, ideas that wouldn’t appear through logic alone. For us, creativity lives precisely in that balance — where the rational and the instinctive meet, and something unexpected emerges that still works perfectly.

Your design approach is positioned in a very clear niche, which gives you a strong advantage in terms of visibility. But not every project brings the same level of attention. Some prioritize impact, while others aim for financial return. What are your main criteria when evaluating a project? How do you balance visibility, impact, and income?

It’s true that we operate within a very specific niche — and that gives us strong visibility, but also particular challenges. It’s easier for us to stand out because what we do is quite unique. However, it’s also a niche where very few people are willing to pay high fees for design. Everyone loves these projects, but unlike residential or commercial buildings, they don’t immediately translate into the same financial returns. So, these kinds of interventions are often treated as secondary, even though they generate incredible social and visual impact.

This dynamic has shaped how we evaluate projects. We usually consider three main criteria:

First, the financial aspect — the fee must make sense and allow us to work properly.Second, the location and visibility — if the project is in a place that will give strong exposure, it may justify taking it even with a modest fee.And third, the client — sometimes a project may not be ideal on its own, but it can open the door to future collaborations that align better with our goals.

Over time, another criterion has become fundamental to me: the project’s public impact. How much does it influence the city and the people who use it?

Early in our journey, we accepted many smaller commissions just to grow. But as we evolved, we began focusing on larger, metropolitan-scale interventions — projects that truly reshape urban life. These take longer to design and build, but their impact is incomparable.

I always say that working in public space is a privilege, because that’s where our reach as designers is widest. It’s where architecture meets everyday life. So when choosing a project, we always ask: how many people will this touch, and how deeply? That’s the real measure of value for us.

In your manifesto, you emphasize the idea of “play in the city,” inviting people back to the streets, plazas, and collective presence. This is not only a design approach but a cultural shift. In regions like Turkey, where cities are mostly planned around speed and functionality, and where most squares are still treated as “transit zones,” how do you think your approach would resonate? In your view, what needs to be reimagined first to create a truly livable city?

We envision the cities of the future as large playgrounds — or better said, as cities that include playgrounds for everyone. Not only for kids, but for adults as well. Our grandparents, our parents, and we ourselves all like to play — we just do it differently. Play is a form of interaction, and interaction defines the quality of life. The more we interact, the happier and even the healthier we are.

In today’s world, where technology often reduces our social encounters to a screen, we believe we need to bring people back to the streets, back to the plazas, back to the physical realm.

But that doesn’t mean rejecting technology — it means using it to create a new kind of public space: playful, livable, and beautiful, where interaction and imagination are central. That’s the kind of city we hope to see — one full of “toys for the city,” spaces that spark curiosity, connection, and joy on a metropolitan scale.

In the case of places like Türkiye, where cities are often planned around speed and functionality, I think our approach would resonate strongly. But it’s not a shift that depends on a single designer — it’s a cultural and political transformation. When we talk about real estate developers or commercial operators, it’s easier: they already understand that public space adds value. Whether it’s a residential compound or a retail destination, a well-designed public realm attracts people, increases sales, and improves reputation.

However, when we talk about city-wide issues, things get more complex. Then it’s no longer about a single project — it’s about urban planning, regulation, and leadership.

To create truly livable cities, everyone must tune in to the same objective. Political leaders need to understand that public space is not just a matter of well-being, but also a driver of tourism, economic growth, and urban development. Once that vision is shared from the top, the transformation can happen.

You are already reshaping the present with highly imaginative projects, but what are the future dreams of 100architects? What kind of projects do you hope to realize in the coming years?

100architects is in constant motion — always evolving. In the twelve years since we started, we’ve gone through several stages of transformation. In the early days, we designed small-scale interventions: temporary installations for summer festivals or retail streets looking to attract footfall. Then came larger commissions in China — projects of 1,000 to 2,000 square meters for residential compounds and commercial developments.

Today, with the recent opening of our Dubai office, we’ve entered a new phase. We are now working on metropolitan-scale projects, taking our concept of hyper-stimulation and urban activation to an entirely new dimension. Our current work includes large waterfront masterplans — sometimes stretching for several kilometers — as well as metropolitan parks, city promenades, and complete streetscapes with integrated street furniture and pedestrian networks.

Across the Middle East, we’re transforming urban landscapes through projects that combine functionality and imagination — creating spaces where people can connect, interact, and enjoy public life again. Just this year, we’ve designed three major waterfronts, each with a unique narrative and a system of activation nodes that bring cities to life.

As for the future, we see this expansion continuing. The advantage of having started so young is that we still feel we’re just beginning. We aim to keep growing — opening new offices not only in the Middle East but in other regions as well, taking our philosophy to different contexts around the world.

We envision designing at even larger scales — projects tied to global events such as the Olympic Games, World Expos, or urban transformations of similar magnitude.

Our dream is to keep creating urban experiences that redefine how people interact with cities — playful, inclusive, and inspiring environments at a metropolitan scale.

Finally, if you had to select three projects from around the world that align most closely with your design philosophy, which ones would you choose and why?

There are several projects around the world that I deeply admire and that align closely with our philosophy at 100architects.

The first one is Superkilen Park in Copenhagen, designed by BIG and Topotek 1. It was a huge inspiration for me early on. That project showed us the power of color and how simply painting the ground — without building walls or adding complex structures — can completely transform the way people behave and interact. It was one of the first times I truly understood how graphic design and architecture could merge to shape public life.

The second one is also by Bjarke Ingels Group: the CopenHill (Amager Bakke) project in Copenhagen — the waste-to-energy plant that doubles as a ski slope and climbing wall. I find it extraordinary. It turns something as utilitarian as a trash-processing facility into a joyful public attraction. BIG calls this approach “sustainable hedonism”, and I couldn’t agree more — it’s architecture that solves real problems while bringing happiness and fun to the city.

The third project I’d mention is Little Island in New York, by Heatherwick Studio. It’s a beautiful example of how public space can be poetic and functional at the same time. It combines green areas, amphitheaters, and pathways in a sculptural form that floats on the Hudson River — a literal “toy for the city.”

And if I may add one more, I have to mention The High Line in New York, by Diller Scofidio + Renfro. It’s one of the most remarkable transformations of infrastructure into public life. By converting an old elevated rail line into a linear park, they created an urban connector that

Comments